Sustainable palm oil requires more than just addressing environmental concerns, although social and environmental impacts are often interrelated. The production of palm oil can result in land grabs, loss of livelihoods and social conflict. The resulting conflicts have had significant impacts on the welfare of many people.

Famers protesting a palm oil companies destruction of their lands, Nigeria © Friends of the Earth

Social conflict

- Conflict can occur between communities and companies over rights to land.

- Conflict can occur between communities and non-native workers (i.e. migrants) who have been brought in to work on the plantations.

- Conflict can occur within communities, due to the income gap created when some villagers experience increased income from oil palm plantations.

Displacement of communities and loss of customary land rights

- According to Indigenous People’s Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN), an Indonesian NGO, indigenous lands cover between 40 and 70 million hectares in Indonesia; however, only 1 million hectares are legally recognized by the government.

- Indigenous peoples’ customary land rights are often not recognised by the state, leading to governments handing over their land to oil palm companies without their knowledge or consent. Villagers have been pushed out of their traditional farming areas; in Borneo, Dayak people who have lived on ancestral forest lands for many generations have been displaced by corporate land grabs.

- In 2008, oil palm was responsible for 27% of total deforestation in one district of West Kalimantan, with commercial oil palm concessions covering 59% of community forests, whether legally recognized or not.

- Without official land titles, indigenous people often get in to conflict with companies for “stealing” resources, such as wood, from land that traditionally belonged to them.

- Displacement of rural farmers can lead them to move on to new areas of untouched forest to clear land for farming.

Dependence on large plantations

- Smallholders (defined by the RSPO as working on plantations of less than 50 hectares) account for a significant proportion of palm oil production in Indonesia and Malaysia (approximately 35–45%), while in Africa and Latin America the majority of producers are smallholders.

- Some smallholders (such as scheme smallholders) are directly managed by the managers of the mill, estate or scheme to which they are linked. However, it has been found that some farmers often struggle to repay the loans issued by large commercial operations.

Loss of cultural heritage

- Culturally important sites can often be lost due to the development of plantations.

- High Conservation Value (HCV) areas include those of global or national cultural, archaeological or historical significance, and/or of critical cultural, ecological, economic or religious/sacred importance for the traditional cultures of local communities or indigenous peoples.

Labour rights

- Workers often live in poor conditions without access to basic facilities such as clean water and lighting, and are isolated by a lack of social support and cultural barriers.

- Some oil palm plantations are dependent on imported labour or undocumented immigrants.

- Trafficking cases have been identified in Malaysian and Indonesian oil palm plantations. Workers often have their passports and other official documents confiscated and are not given proper contracts. They can face abusive conditions and can be threatened with deportation or confiscation of wages.

- Child labour is a common problem in Malaysian and Indonesian oil palm plantations. Children receive little or no pay and may be forced to endure harsh working conditions including long hours and exposure to toxic chemicals. This can be driven by poor education, a lack of school facilities and a generally low regard for education in rural areas.

- In Malaysia, it is estimated that between 72,000 and 200,000 stateless children work on palm oil plantations.

Loss of livelihood

- More than 50 million Indonesians depend on the forests for their livelihoods.

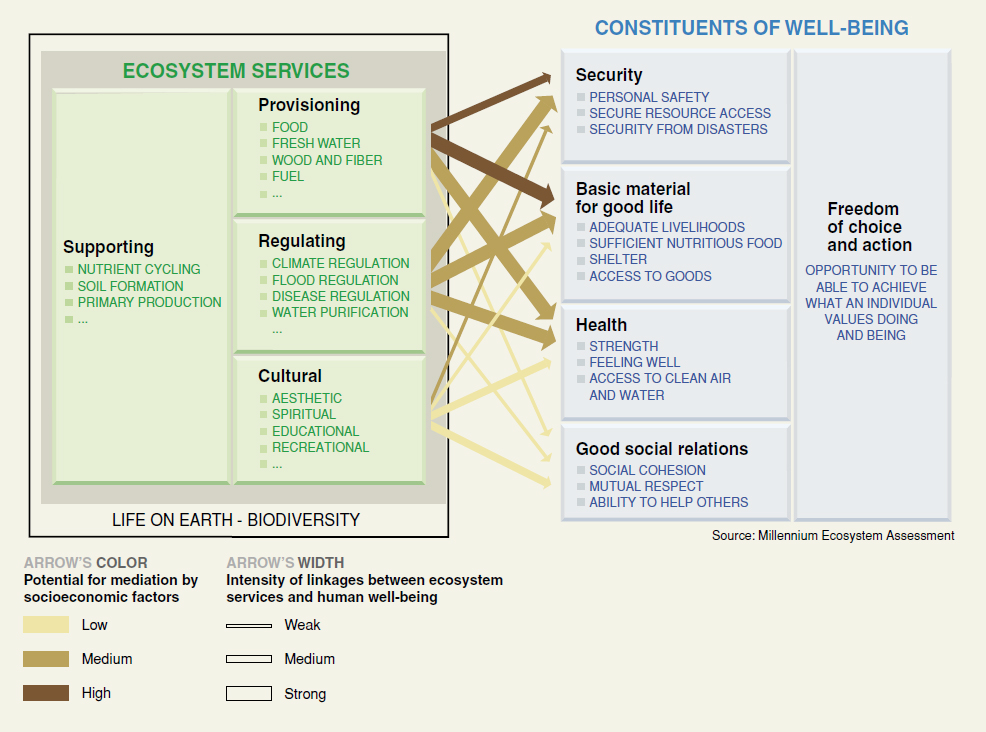

- Communities rely on forest resources for a range of nutritional and medicinal purposes. Deforestation destroys essential ecosystem services like the provision of clean water and fertile soils, leading to the loss of farming and other livelihood opportunities, such as fishing and hunting for food.

- Displaced communities are forced to farm further away from towns, which restricts their access to markets for their produce, as well as their access to basic services such as health care and education.

- Deforestation also reduces access to land for future generations held under customary tenure.

Health

- Water pollution due to over use of fertilisers and pesticides on plantations can affect the quality of drinking water.

- Uncontrolled burning for plantation expansion can have widespread health and socio-economic impacts. There were an exceptionally high number of fires in Indonesia in 2015, particularly in Sumatra and Kalimantan. The resulting haze had dramatic effects on local populations, reaching as far as Malaysia and Singapore.

- At times during the 2015 haze crisis, pollution levels in areas where fires were burning were recorded at over 2000 on the Pollutant Standards Index – far above the 300 which is considered ‘hazardous’. There were over 500,000 reported cases of respiratory illnesses in 2015 and 19 people died in Indonesia alone.

Resources

Reports

- Assault on the Commons – Deforestation and the denial of forest peoples’ rights in Indonesia

- Costs of Company-Community Conflict in the Extractive Sector

- CRUEL OIL How Palm Oil Harms Health, Rainforest & Wildlife

- Environmental and Social Impacts of Oil Palm Plantations and their Implications for Biofuel Production in Indonesia

- Exploitative Labor Practices in the Global Palm Oil Industry

- Forced, child and trafficked labour in the palm oil industry

- Free and Fair Labour in Palm Oil Production: Principles and Implementation Guidance

- Palm oil and indigenous peoples in South East Asia

- Palm oil, land rights and ecosystem services in Gbarpolu County, Liberia

- Securing Rights, Combating Climate Change – How Strengthening Community Forest Rights Mitigates Climate Change

- The Cost of Conflict in Oil Palm in Indonesia

- The Economic Costs And Benefits Of Securing Community Forest Tenure: Evidence From Brazil And Guatemala

- The Financial Risks of Insecure Land Tenure

- The great palm oil scandal: Labour abuses behind big brand names

Articles

- In Borneo’s Ruined Forests, Nomads Have Nowhere to Go

- Palm Oil Giant Kuala Lumpur Kepong Berhad (KLK) Plagued By Ongoing Conflict and Exploitation

- Body Shop drops supplier after report of peasant evictions in Colombia

- Indonesia’s Palm Oil Industry Rife With Human-Rights Abuses

- 3 Ways to Strengthen Customary Land Rights in Indonesia

- Promised task force on indigenous rights in Indonesia hits snag

- Govt ready to distribute customary lands

- Philippines Islanders Unite to Resist “Land Grab” Palm Oil Companies

Last updated: 24/11/2016